Featured Artists

Mark Madden

Mark Madden has long viewed owls as “mystical and magical,” inspiring him to create compelling photographs and wood carvings. The new Valley Artisans Market artist finds the raptors’ charismatic expressions and calls to be an endless source of fascination. “Owls are associated with spirituality, wisdom, and omens in many cultures,” he notes, including Greece, where the owl symbolizes Athena, the goddess of wisdom.

Madden’s carvings are lifelike, painstakingly executed images that capture these birds in their full magnificence. He believes his carvings have benefited from his years of studying and photographing owls in the field. His photographs are available both as framed prints and smaller cards and feature many different varieties. One, a Red Screech Owl, peers out of its knothole against the full moon while a Snowy Owl perches on a rocky coastline by a lighthouse.

Madden travels all over New England and New York State in search of his subjects. Last year, he went to northern Maine to get pictures of a Northern Hawk Owl and last winter found him in Canada, where he saw several Short-eared Owls and Barred Owls. He’s also a regular at the Washington County, NY grasslands, where Short-eared Owls and Snowy Owls (in winter) abound.

“It’s an adventure taking pictures of owls,” Madden says. Often heard at night but rarely seen, they’re elusive because they don’t like to be around humans. “They are usually sleeping during the day, so you have to wait until evening for them to wake up and open their eyes.” The next challenge is getting them out of their nest hole. He eschews using calls because that can disturb and attract other owls that may be predators. Instead, he just waits patiently. Owls are most active late at night and in the early morning, giving him an hour’s window of good light. But sometimes he faces the technical challenge of nocturnal photography, which means multi-second exposures in nearly complete darkness.

Madden’s studio is in his home in Bennington, VT, with one room devoted entirely to woodcarving. “Then I take over the kitchen table to paint my birds,” he says. “It’s always a challenge to get a nice, soft look.” He uses an airbrush and light washes to slowly build up the colors.

With a graphic arts background, Madden worked in the printing industry for many years. He is largely self-taught, poring over books and also taking seminars from other carvers to learn different techniques. “The best thing, though, is studying the birds directly in the wild. Nothing is better than seeing the bird in its natural setting,” he says.

Accordingly, Madden asks that if you see owls in your area, contact him if you’re willing to let him come over and photograph them: obsessedwithowls@comcast.net.

– Nancy Roberts

Erin Sheridan

Wherever Erin Sheridan goes, she keeps an eye out for the eclectic items that grace her cotton clothesline rope baskets. Peacock feathers, felted flowers, vintage jewelry, geodes, and even antlers adorn the unique vessels she creates in her Hummingbird’s Heart Studio located in White Creek just outside Cambridge, NY.

Wherever Erin Sheridan goes, she keeps an eye out for the eclectic items that grace her cotton clothesline rope baskets. Peacock feathers, felted flowers, vintage jewelry, geodes, and even antlers adorn the unique vessels she creates in her Hummingbird’s Heart Studio located in White Creek just outside Cambridge, NY.

Erin’s background is equally eclectic. A college English and Journalism major, she joined the Air Force and worked as a Crew Chief on B-52 bombers in the late 1970s. Eventually, in 1989, she became a real estate agent and broker, also working as a NY State certified real estate licensing instructor and continuing education creator.

But she was always drawn to artistic pursuits. Her mother, a musician and accomplished chef, opened a restaurant and bar in the area in 1969 and there taught Erin culinary skills, including baking and cake decorating. This led Erin to establish her own catering business for a time. Her mother also taught her to sew, a lifelong passion.

“I love the sewing process,” Erin says. “Once I start to build my basket, the repetitive motion is very calming to me. None of the baskets are ever the same—they start to take on their own shape and personality as I work on them.” She sometimes uses her commercial embroidery machine to create the bases for the baskets. She enjoys digitizing some of her original designs for her machine to “read.” Current examples include a loaf of bread (for a breadbasket, of course) and a tree of life. It was worth it, she says, to travel to Chicago twice to learn how to use the required software.

Erin’s passion is to make her baskets functional, as well as ”pieces of art that everyone will enjoy.” She especially loves using unique elements from nature and incorporating them into the exterior of the basket. “Sometimes the decoration is the very first component. If I find an interesting piece of bark or a cluster of unusual moss or feathers, it will inspire my basket’s design.” A challenge she faces is finding the right quality rope, because most rope these days is made of plastic or other synthetics. Another challenge, she says, laughing, “is not breaking 20 needles on one basket.”

Erin has always been a “maker of some sort,” as she puts it. While working at a quilt shop in Saratoga she taught classes in quilting techniques, design and color theory. Over the years, she has also taken classes with different artists in a diverse variety of mediums, including quilting, weaving, fabric dyeing, and printing. She enjoys making paper beads and jewelry from junk mail and creates art quilts using her hand-dyed fabrics and felted wool. Many of her artistic creations have always involved sewing of some sort, but baskets were a “What if!” moment for her. She says, “My attitude has always been, you can’t fail unless you try. Although I’ve failed miserably at some things, I’ve mostly enjoyed much success at others, and doesn’t that make it all worthwhile?”

– Nancy Roberts

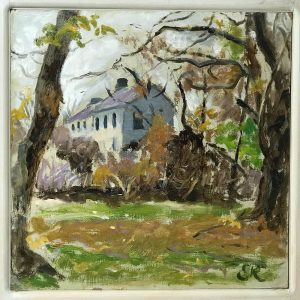

Featured artist: Jean Clark

Jean Clark’s environmental portraits of animals are engagingly intuitive. A goat munching dandelions peers placidly at the viewer in a colorful monoprint, while in another, a great ape savors a ripe banana. The coy gaze of a hippo by a riverbank seems nearly human, while a squirrel ‘s delight at a trove of acorns is almost palpable.

Then there is the small black dog with foxy ears, a frequent figure in Clark’s work. Whether shown exploring the wider world or homeward bound, Clark’s depiction of the little canine nails the specie’s characteristic curiosity—and loyalty. “We’ve always had dogs,” she explains their lure as subject matter. “I simply observe them at home.” In fact, her 12-year-old rescued black Labrador retriever, Tucker, is her occasional muse.

Viewers have often remarked on the whimsy and sense of wonder in Clark’s work. Joy is implicit.

Another frequent subject in Clark’s art is houses. In bright, warm colors, she captures their allure as a place of respite, of home. In “Reflections,” she shows how their images ripple into the peaceful void of a lake. “Houses are my portraiture,” Clark explains.

Another favorite subject is weather’s many moods, as in the monoprint “Stormy,” which captures the swirling drama of thunderstorm clouds.

Clark grew up in the suburbs of Westchester NY, one of eight girls and five boys. She recalls “being serious about art” from an early age. There in the Greater New York area, she remembers that “my inspiration was graffiti. I lived on a small island in the Bronx and loved the daily commute into the city, with pop art by Keith Haring all over the sidewalks and on the subway walls. It got me excited about fine art and the Neo-Expressionism movement that was emerging in the late 1970s and into the ‘80s.”

In high school, she studied commercial art and a teacher’s mentoring led her to get a scholarship right after graduation to the Art Students League. Subsequently she enjoyed a career designing stained glass reproductions for museum gift shops and the gift trade.

After years of downstate life, she and her husband relocated about thirty years ago to the outskirts of Greenwich, NY, where she finds the rural lifestyle congenial to her creativity. Long a perennial gardener, she’s nurtured Lenten roses (Hellebores), yellow irises, and the tree -climbing hydrangea. Perhaps not surprisingly, flowers occasionally show up in her art, such as a lush bouquet of blush roses in a blue checked vase.

Clark’s work has been exhibited in many local venues, among them the Saratoga Arts Center, the Troy Arts Center, Lake George Arts Project and the Agricultural Stewardship Association’s “Landscapes for Landsake” show. An important influence has been taking printmaking classes with Sunghee Park, an instructor at the Troy Arts Center. “She was so inspirational,” Clark says. “Having such a wonderful teacher just drew me to printmaking. I found that it’s an exciting process with a whole series of steps involved that I immediately took to. I really do enjoy the whole process of printmaking, step by step.”

Clark’s work has been exhibited in many local venues, among them the Saratoga Arts Center, the Troy Arts Center, Lake George Arts Project and the Agricultural Stewardship Association’s “Landscapes for Landsake” show. An important influence has been taking printmaking classes with Sunghee Park, an instructor at the Troy Arts Center. “She was so inspirational,” Clark says. “Having such a wonderful teacher just drew me to printmaking. I found that it’s an exciting process with a whole series of steps involved that I immediately took to. I really do enjoy the whole process of printmaking, step by step.”

Welcome New Member, Susannah White

Felting is the oldest known manipulation of the natural world. It is older than stone work, basketry or claywork. That is because wool doesn’t require human intervention to felt; the wool of a sheep’s coat, for instance, is naturally felted.

Susannah White theorizes that early humans recognized this quality and were immediately drawn to felt’s versatility.

The natural process of turning frayed fibers into a solid piece of fabric is only a short leap to stunning artwork. Susannah herself has mastered that process.

Susannah began working with fibers more than five decades ago. “Our family had a farm where we spent most of time when not in school. Our neighbors were sheep farmers and I started playing with their wool back in the 1960s.” Because she loved everything textile, she discovered felting on her own. When she saw a museum exhibit featuring felted wool from an ancient tomb in China, her life’s calling was realized. As a young felter, she absorbed everything she could about the process.

Susannah describes felting as a physical change in fiber. “Any protein has scales along the fiber. You aggravate the fiber with hot water and [then add] something annoying to the fiber – like soap – which causes the scales to open up. You use your hands by massaging, rubbing, and pounding the fiber, which makes the scales lock on to one another. Once in cold water, everything contracts and locks and makes a permanent change in the fiber,” she explains.

For Susannah, felting came by way of weaving (starting with her first loom at age 13) and textile design in college. With the birth of her children, however, Susannah didn’t have the luxury of time to warp a loom. She returned to felting by fashioning felted toys for her kids. “I believe strongly that children should have the most carefully made objects in their life,” she maintains, “and the objects most thoughtfully done should be for children.” “When I was young, my dad traveled all over the world and would bring back puppets. He built a puppet theater. There was one thing that frustrated me: he gave me Steiff hand puppets. They are fun to work with but when you removed your hand, all the life left them like a deflated balloon. I was always sure to make puppets so they retained some life force. I wanted my puppets to have a lively aspect whether or not they are in use,” she says.

To be sure, her passion for shepherding, feltmaking, quality craftmanship, and puppet artistry all intersected in her unique work.

Susannah’s puppets and performing objects are made from the wool of family or friends’ sheep. The vibrant colors, she says, come either from plants or from the natural color of the wool. “Because I work in textile design, I am aware of the carcinogenic and mutagenic qualities of commercial dyes. Plant dyes are relatively harmless, depending on the mordant used. I only use alum and cream of tartar. The colors are very beautiful— they can be very intense or very subtle — and have a distinctive living quality to them. They complement one another. Each year I grow or wild harvest more of the plants I need for color,” she says. Indeed, at this point, Susannah only purchases three plants for dyes: indigo, brazil wood and madder. And this year, experiments with growing indigo began in the Cambridge Community Garden. “We successfully grew and harvested fresh indigo and dyed both wool and silk, though only in small amounts. We’ll see if we can increase the amount of color we get next year.”

Susannah’s puppets and performing objects are made from the wool of family or friends’ sheep. The vibrant colors, she says, come either from plants or from the natural color of the wool. “Because I work in textile design, I am aware of the carcinogenic and mutagenic qualities of commercial dyes. Plant dyes are relatively harmless, depending on the mordant used. I only use alum and cream of tartar. The colors are very beautiful— they can be very intense or very subtle — and have a distinctive living quality to them. They complement one another. Each year I grow or wild harvest more of the plants I need for color,” she says. Indeed, at this point, Susannah only purchases three plants for dyes: indigo, brazil wood and madder. And this year, experiments with growing indigo began in the Cambridge Community Garden. “We successfully grew and harvested fresh indigo and dyed both wool and silk, though only in small amounts. We’ll see if we can increase the amount of color we get next year.”

“If you are looking at old rugs or tapestries and see that beautiful rose/salmon color,” she says, “that’s madder.” (One time she accidentally fermented some madder. Not wanting to waste it, she threw some wool into the dye and was delighted to get a brilliant red from it!) It is the capricious unpredictability that makes dyeing with plants so fascinating and lively for her.

Currently, she is most delighted by making sweet and simple mouse and chicken finger puppets and never tires of these characters. “Part of being a craftsman is that you spend your life developing your skill and then you spend whatever remains of your life just doing it. It is not my goal to make anything different. My goal is to make everything well. I’m at the phase in my life when I know what I am doing,” she says. But even after 40 years of working with felt, she has still taught herself more. She has recently learned that the tighter a puppet is on one’s hand, the more control one has.

Susannah is not just the artist behind the scenes. Three generations of her family, collectively known as Dancing Hands, give performances to audiences for free, though COVID has postponed most performances over the past 20 months. She takes pride in trying to preserve a heritage craft.

In summing up her craft she says, “There’s that saying that one person can’t change the world. But one person can make felt, which is a permanent change.”

Welcome New Member, Elizabeth Roberts

Viewing and creating art has intrigued Elizabeth Roberts since her earliest days. She recalls being fascinated as a kindergartener by the paintings her artist mother took her to see at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Art Institute in Utica, NY. A special treat was lingering in the museum’s store, where she would use her allowance to buy the polished agates that looked like miniature landscapes to her.

Viewing and creating art has intrigued Elizabeth Roberts since her earliest days. She recalls being fascinated as a kindergartener by the paintings her artist mother took her to see at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Art Institute in Utica, NY. A special treat was lingering in the museum’s store, where she would use her allowance to buy the polished agates that looked like miniature landscapes to her.

Later on, she says, “I doodled my way through grade school and high school.” Her specialty was secretly creating ballpoint pen caricatures of classmates and teachers that even included moving parts, such as a cardboard insert that could be shifted back and forth to suggest darting eyes.

While majoring in psychology at the State University of New York at Oswego, she also took a few studio arts classes “because they sounded interesting.” After college, she signed up for a course in painting at Syracuse University where she created a work she says she’ll never forget: The Egg Painting. The instructor assigned the students to paint a still life consisting of six eggs sitting on an old dark wooden table. Elizabeth dutifully used her palette knife to mix up what she thought were “eggy colors,” of cool and warmer grays. “I didn’t know how to blend colors yet, nor to look in a mirror to check if the perspective was skewed,” she says. Nor had she learned yet how to use a paintbrush, so she simply mushed the oil paints in with her palette knife. The result was a scene of “ugly little eggs drowning on a huge table that leaned to one side, with a solid background of cream-colored paint with no gradation whatsoever.”

She laughs, recalling how she wanted to destroy the painting. But her father, a teacher, suggested that it was so awful that she should keep it to remind herself and show others that improvement is possible.

Some 40 years later, Elizabeth has kept this, her very first painting, for just this reason. “It taught me that you can drown in oil paints if you don’t keep control of them,” she says. She went on to earn a master’s degree in painting at the State University of New York at Albany. “That’s where I really learned to paint,” she says. “All of the classes helped me to learn not only from my own mistakes and successes, but from everyone else’s.”

Over the years, between working with those with developmental disabilities and, until she recently retired, caring for the elderly, Elizabeth has continued to paint in oils, pastels, and acrylics. She’s particularly drawn to the rolling rural landscapes of Washington County and its venerable vernacular buildings. But she also likes to paint portraits and fantasy landscapes. She has exhibited her work in various locales in her native central New York State, including the Munson-Williams-Proctor sidewalk art shows, the State University of New York at Morrisville library, and in a Minneapolis gallery. One memorable exhibition was a joint effort with her late mother, Doris Pellettier Roberts, a watercolorist, at the Morrisville library. “I learned so much from Mom,” Elizabeth says. “She was my most constructive critic.”

She is grateful for all of the trips to art museums that her mother provided. “A good museum gives you an idea of the possibilities,” she says. “Mom would walk with me as I looked at all the paintings, like Thomas Cole’s “Voyage of Life” series, which I loved as a kid. You could get lost in the landscapes, in another world, a beautiful fantasy.” Another early favorite was William Harnett, whose 19th-century trompe-l’oeil still lifes of everyday objects looked so realistic that “you could reach out and touch them, with amazing highlights that he piled on.”

Another childhood influence was the public library, to which her mother often took her. There Elizabeth reveled in the art books, which introduced her to innumerable artists and styles. “I’m still reading books on art constantly,” she says. “If I get any more, my studio (in Saratoga Springs) will collapse from the weight.” A longtime favorite is George Inness, whom she describes as “not just a landscape artist, but a visionary.” She is drawn to “the mystery in his paintings; they hold you captive with their dreamy quality. The colors are beautiful and perhaps the places are recognizable, but transmuted into being a state of mind, or awareness of God, a spiritual feeling. Everything isn’t spelled out; you get caught up in his landscapes.”

She finds inspiration in “a play of light and color that I might see, classical music [Rachmaninoff is a favorite], my internal emotional state, words or ideas that suggest feelings or visual metaphors, and even a random set of marks that can suggest a scene or figure.” A random mark could be something as simple as a pattern in the kitchen linoleum, she notes, pointing to DaVinci’s suggestion of finding inspiration “in random things around you,” such as the patterns in peeling paint.

To jumpstart inspiration, Elizabeth finds that “a bit of extra energy kickstarts being creative, so I prescribe coffee for myself and off I go.”

For her, the most enjoyable aspect of creating art “is experiencing the state of flow where one isn’t really directing oneself so much as forgetting about oneself and letting the work take you where it will. It’s almost as if someone else made the work and I get to be surprised at the end when I wake up from the trance and see what I’ve created. It’s fun to surprise yourself and create something you didn’t think you had it in yourself to do.”

She adds, “I love doing art because it can be all things; it’s a means of communication that has the scope to encompass and distill anything in the world and hopefully be beautiful and meaningful in the process.”

This is an artist who likes to make “anything and everything, from painting portraits and landscapes to making finger puppets and tiny, illuminated cardboard houses.” As she explains, “It’s hard for me to stay in the box. I like to mix things up and try new things.” Always experimenting, she recently started making prints with gelatin plates. She also paints little scenes and affixes them to the bottom of a piece of plexiglass and then paints another layer over the top. “It’s painting on two different planes,” she explains, “and it gives a three-dimensional effect.”

Her biggest challenge is “my own perfectionism, which is not fun to experience but on the other hand, it drives me to constantly try to surprise and surpass myself in everything I do. I just want to keep getting better. And also spread the joy of creating art to viewers.”

Welcome new member Kristina Martin

Empty branches may be beautiful but for Kristina Martin they are a photo failure. It’s the birds that have just vacated the branches that she is hoping to photograph. “I take a lot of photos to get to the good one,” she says.

Empty branches may be beautiful but for Kristina Martin they are a photo failure. It’s the birds that have just vacated the branches that she is hoping to photograph. “I take a lot of photos to get to the good one,” she says.

Her interest in birding started in 2016, after a 30-year career as a medical transcriptionist. Lured by the songs and chirps, flights and feathers of birds, she picked up a camera in order to capture their images to identify these fast-moving creatures and study them more closely. As she began photographing them, she discovered their quirky secrets: the catbird loves to splash and bathe; the wings whistle when the dove takes flight.

“I ended up with all these photos. So I made cards for family and friends. They said they were pretty good! I put together a basket and put them on the counter at Yushak’s (general store in Shushan, NY) and that’s where it all started,” she says.

Kristina loves nature and being outdoors; she doesn’t mind how challenging photographing wildlife can be. Recalling a recent evening in Fort Edward, I can hear a smile in her voice. She hunkered down in the tall grass and waited for short-eared owls that have migrated locally from the arctic to appear. Owls are a favorite subject of hers to shoot partially because they are nocturnal; it’s difficult to get a good shot in natural light. “They came out at dusk and were flying over the grasslands,” she says.

Her work has grown into an extensive line of cards but she also offers enlarged prints and framed art. As customers have requested, she has expanded her work into nature scenes and rural living, including florals, barnyard scenes and covered bridges. (She had a fox family in a hedgerow behind her house last year. She set up a blind and was able to watch four kits grow up while getting great photos for her cards.) She plans to package her cards into gift sets and will create groupings of birds, flowers and more for Mother’s Day and springtime.

Her art is transforming as she gets more practice. She introduced photos that are more abstract. “It’s fun to see people’s reaction to my more abstract work. Some people really get it,” she says. For instance, she took a photo of a snow bend with trees and altered it into sepia. There’s a path that’s lighter than the surrounding area. “It’s nature but it’s funky,” she says.

Although Kristina tries to keep photos as genuine as possible, she uses digital technology, specifically Lightroom, a photography platform, to facilitate the finest result. “I try to make sure the photos I take are the best they can be to start, depending on the conditions. Editing or enhancing photos is part of the craft, improving on the original photo, creating more definition by cropping or enhancement,” she says.

Kristina is enjoying being a relative novice, always learning something new. She appreciates the feedback she receives from her customers as well as tips from other photographers.

Kristina is happy to accommodate specific bird photo requests. She also offers enlargements of any images seen on her Whistle Wing Print cards. “Creating hand-crafted cards and prints allows me to share the beauty, charm and humor I see around me every day.” In the meantime, Kristina will keep on getting outside and shooting … hopefully not another empty branch.

Carol Law Conklin

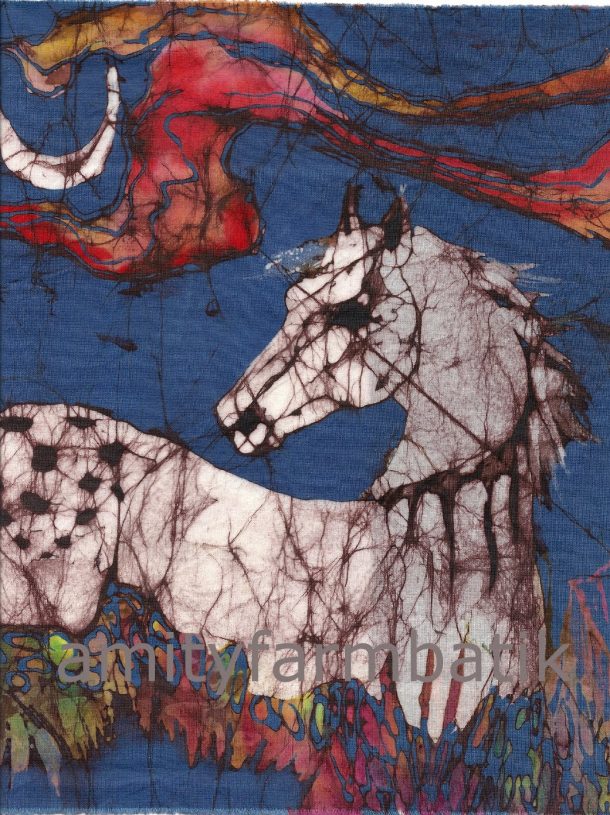

Member Carol Law Conklin, of Amity Farm Batik, writes about making batik using bleach while enjoying the summer weather:

Losing the color

It was a beautiful summer morning. Hazy and not too hot. The gentle breeze felt good as I stood at the top of the hill behind our house. Mist slowly rose and changed the soft colors of the expansive view. The mountains, arranged in subtle layers of blues, greens and purple formed the backdrop as birds and insects fill the air with their music. There is so much life this time of year. Back at home, I’m contemplating the colors I want in several batik that have already gone through many dyebaths. As the dyes are translucent, there are limits to overlays of opposite colors. In order to achieve what I want it will be necessary to bleach out some areas before the desired color can be added.

The summer weather is the best for doing discharge dyeing (bleaching). This process is something not to be done inside. The bleach, which removes the color wherever the wax has not been applied to save the design, has quite strong fumes. To stop the bleaching action, I plunge the fabric into a solution of water and vinegar, gently agitated and left there for approximately 15 minutes. This produces more toxic fumes. The commercial product, “Bleach Stop” (sodium thiosulfate crystals), is even more effective, but I believe have stronger fumes. A respirator mask is recommended when working around toxic fumes and good ventilation is essential.

Different dyes and intensities of dye bleach in a variety of unpredictable ways. When using strong solutions for bleaching deep colors be extra careful. Acid and chlorine combined can kill! Monitor and stir the fabric as it bleaches. Various fabrics and dyelots take different times. Blue seems to bleach out overly quickly and thoroughly. Some colors change to a new color and not beige or white. Silk can stand only very weak bleaching without causing the fabric to deteriorate. Vinegar has an additional bleaching action and results are unpredictable as well as fascinating.

The photos show a batik in the bleaching tub, after bleaching and finally you can see my “Appaloosa Horse in Flower Field” at the top of the page after the re-dyeing and with the wax ironed out, bright and expressing the summer season.

Find more batik, articles and tutorials on Carol’s website: www.amityfarmbatik.com

Welcome to our new member, Nancy Roberts

The exhilaration of creating a piece of mosaic art led Nancy Roberts to momentary amnesia. Any mosaic artist knows that handling sharp-edged glass is an inherent danger of the form. But enraptured by the stunning iridescence of her new creation, she forgot to wear protective gloves and smoothed grout over the artwork with her bare hand. The resulting small slashes kept her from playing the piano for a week.

The exhilaration of creating a piece of mosaic art led Nancy Roberts to momentary amnesia. Any mosaic artist knows that handling sharp-edged glass is an inherent danger of the form. But enraptured by the stunning iridescence of her new creation, she forgot to wear protective gloves and smoothed grout over the artwork with her bare hand. The resulting small slashes kept her from playing the piano for a week.

Such passion is typical of creatives. Like most of them, Nancy has worked or expressed herself in some artistic way all of her life: She has written for art magazines, published her photography, designed cottage gardens and taught the history of early American architecture. (You can see the influence of architecture and her garden in her work.) And her curiosity has propelled her in many new directions. She has recently taken up the dulcimer and, of course, mosaic art. Taking a course from a local mosaic artist, Nancy immediately loved it. “It blew me away,” she says.

Tables are her favorite item to mosaic at the moment. “People throw them out and I love getting them re-glued and repaired.” Then they become a blank canvas for myriad designs in glass. She notes how a different architectural quality is evident in every table, such as old iron nails or a gracefully tapered shelf. “I try to make them look really beautiful again,” she says. She also mosaics mirrors, flat wall decorations and even a mail sorter currently hanging at VAM.

Nancy buys her materials from stained glass supply and DIY stores, often online, and she discovers mosaic materials in unusual places. A salvaged piece of a stained-glass window from a Victorian house in Saratoga Springs eventually found its way into a work titled Homage to Notre Dame, which is on sale at VAM. She also incorporates sea glass, porcelain and mirror tiles, sea shells, and vintage crockery in her work.

She enjoys the challenge of hunting down the right scraps from stained glass stores and then using those little fragments to create. Such bounty is plentiful at these shops and you can buy a boxful for a modest price, she says.

One source of her inspiration is the rolling countryside of Washington County, with its farms, fields, wetlands, and wildflowers. In fact, her next frontier in mosaics may well be landscapes, with smaller and more intricate designs. Inspiration also comes from the pleasing lines of historic architecture. Having studied early American architecture, Nancy says, “I can’t walk down the street without seeing the intricate details of houses and I see that wherever I go.” Much of her inspiration is from her extensive garden (where she grows pawpaw fruit trees as well as vining Arctic kiwis and kale). Favorite flowers — rose campion, irises and daffodils — grace some of her work. The natural world is her muse, leading her also to portray seascapes and the brilliant forms of butterflies. The adventure of learning something new sings in her voice and her eyes when she speaks about any of her creations.

The late Virginia McNeice

Founding VAM member Virginia McNeice, 82, died on March 12, 2019, surrounded by her loving family. Virginia was the beloved wife of Donald McNeice. Born July 17, 1936 in Riverdale, N.Y., she was the daughter of the late Harold and Maude (Taylor) Paro. Virginia (Jini) attended Pratt Institute of Art in Brooklyn, N.Y., graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Art. In 1966, the family moved from Huntington, Long Island to Cambridge, NY to pursue their dream of living on a farm with their family.

Founding VAM member Virginia McNeice, 82, died on March 12, 2019, surrounded by her loving family. Virginia was the beloved wife of Donald McNeice. Born July 17, 1936 in Riverdale, N.Y., she was the daughter of the late Harold and Maude (Taylor) Paro. Virginia (Jini) attended Pratt Institute of Art in Brooklyn, N.Y., graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Art. In 1966, the family moved from Huntington, Long Island to Cambridge, NY to pursue their dream of living on a farm with their family.

Jini became a prolific and regionally-renowned landscape artist who drew inspiration from the natural beauty of the countryside she loved. Her work is in private collections, regional galleries, local hospitals and businesses. Jini’s art moved many people and even inspired some to begin their own artistic journey. Her artist friends valued her knowledge and insight, as she welcomed them into her studio and her life. As celebrated as she was in the art world, Jini accepted accolades with humility and grace. A quotation on her studio wall reads, “It’s the process, not the product”. Jini enjoyed being a vital member of the Cambridge community, Valley Artisans Market, Hubbard Hall, Battenkill Chorale, and the Agricultural Stewardship Association. Her calendar was always full.

Visitors to her studio were drawn to her gardens, which were one of her personal passions, and on hot days she would alternate gardening with dips in the pool. Jini and Don knew that gathering and growing their family around them was another expression of art in its finest form. Family extended far beyond blood relatives: they frequently opened their home to their children’s friends, young artists, and friends with shared interests. Jini was generous with cuttings from her garden, a quick art crit or a recommendation for a good book to read. The McNeice home was always open and the table always full. In the early years Jini and Don were proud to produce all their own food for the table, and in later years Jini always had a large vegetable garden, which she shared with family and friends and, to her great annoyance, woodchucks and rabbits.

Her children write, “Our mother taught us to see and appreciate color and light in the landscape around us. She taught us the pleasure of putting our hands in the dirt and making something beautiful. She encouraged in us her love of poetry and words, from juicy, descriptive phrases in a novel to a particularly witty wedding announcement in the Times, to a poignant line in a Mary Oliver poem. We learned to be curious and hardworking; to follow our passion; and to value family above all.”

Virginia was predeceased by her husband Donald of 54 years. Survivors include four children, Maggie McNeice of South Portland, Maine; Brian McNeice and his wife Jenny Ramstetter of Halifax, VT.; Kathy McNeice and her husband, JR Dugas of Cambridge; Annie McNeice of Cambridge; her sister, Diana Schleicher of Greenwich, NY; and many nieces, nephews and eight grandchildren. If you would like to remember Jini in a special way, the family suggests a donation to a Hubbard Hall or the Agricultural Stewardship Association.

New Member Emily Crawford

Emily Crawford dreamed of working as an undercover agent. She attended Hamilton College with the intention of being recruited to the CIA. But instead of becoming a spy, she pursued what she did best: art. She graduated with a degree in studio arts with a concentration in sculpture.

Emily knew she would find her way back to art, but first she had many other paths to follow. (During one of those paths, she worked as a website designer for 17 years. She helped design and build VAM’s website.) But after a recent job change, her attitude shifted. She prioritized art and career together.

She joined a friend at a class at the Saratoga Clay Arts Center in Schuylerville. When she put her hands back into clay for the first time in 30 years, she found her way back home.

“When you are an artist at heart, you are always creative in your life: the meals you make, the Halloween costumes you sew,” she says. But once she felt that clay, she didn’t want to get another job supporting creatives in their dreams. She wanted to put her artistic life front and center in her career, as well. She gave herself six months to delve deep into growing her own creative business. She rented a studio at Saratoga Clay Arts, built a web site, took classes for artists building creative businesses and began throwing clay. It worked. People are purchasing her work and she is refining it, and growing an learning more every day.

Her childhood home in Nova Scotia is the inspiration for her clay creations. “Everything I do is nautically inspired. I grew up going to Nova Scotia every summer and I stayed in our ancestral home. It is right on the Sissiboo River, off the Bay of Fundy.” The place she describes sounds magical. There are 40-foot tides, which allow for abundant beach combing. “On one beach, you have to walk a quarter of a mile to reach the ocean when the tide is out. There are all these tidal pools with seaweed floating around,” she says as she takes out a celadon green bowl, inspired by those pools.

In the summer the ocean is “a deep, deep green, almost an emerald. But then the ocean dramatically changes color from summer to fall. It turns a beautiful blue,” she says. She picks up a mug with colors graduating from black to a deep blue.

Looking closer at Emily’s pottery, one can see colors, textures and patterns based on the ocean. There are splashes and ripples, and mottled areas that look like sand. She points to drippy areas resembling waves lapping on the beach. The names of her pieces reflect her inspiration: Atlantic Splash, Sissiboo Tides, Beach Waves, Northern Lights, Fog.

Using Nova Scotia as her entry point into imagination and creation, Emily finds new ideas not only from the colors but also the shapes she sees. She makes “buoy bowls” that look like vases but the bottom resembles a buoy shape. On one of the buoy bowls, she pressed netting into the clay for texture. “I get so much inspiration for new textures in my work from beach combing.” And it’s hard to ignore the three-foot high sculpture of a lighthouse on her studio work table. If all goes well in the kiln, this piece will be the focal point of her upcoming show in the Small Gallery.

The lighthouse is simple, with just three flying birds etched into its side. She etches or paints the same birds into all the pieces she makes, a sweet reminder of the ocean and sand and tides. “That’s the core of who I am. The ocean – and my time in Nova Scotia – is my soul.”

In the future, she would love to create a Washington County series. She envisions visiting farms and using the inspiration she finds there to throw undiscovered shapes on her portable wheel. She hopes to join the ASA show and see the sale of her work go towards saving local farmland.

Her work may not involve the exciting life of espionage for the CIA but it fulfills her completely. She has never been happier.

Emily’s high-fire bowls, mixing bowls, mugs and other food-safe pieces are dishwasher- and microwave-safe. Emily has the next show in the Small Gallery, March 22-April 16. Her opening reception is March 30, 3-5 pm.